Photographer: Yuri Smityuk/TASS/Getty Images/TASS

Every few years, someone comes along promising to disrupt the satellite industry. They burn through billions in cash before ambition crashes back down to Earth. Since the late 1990s, Globalstar, Iridium, Leosat, Skybridge, Teledesic, and other companies have attempted to rewrite space communications, only to collapse or shrink into a niche that poses little threat to the incumbents.

Now comes Elon Musk. After overturning the economics of the car and the rocket-launch industries, the billionaire is taking a hatchet to another fraying business model—space communications—by filling the skies with thousands of satellites that beam internet to isolated populations. His Space Exploration Technologies Corp. sent up the first Starlink satellites in May 2019, and as of early this month it had deployed almost 700, single-handedly increasing the number of active satellites in orbit by almost a third.

Broadband from space already exists, but it relies on geostationary satellites that orbit more than 22,200 miles from Earth, making the connections too slow to compete effectively with new applications on terrestrial networks. By contrast, Musk’s are at an altitude of 340 miles, putting his system at a potential speed advantage over the fastest undersea fiber networks.

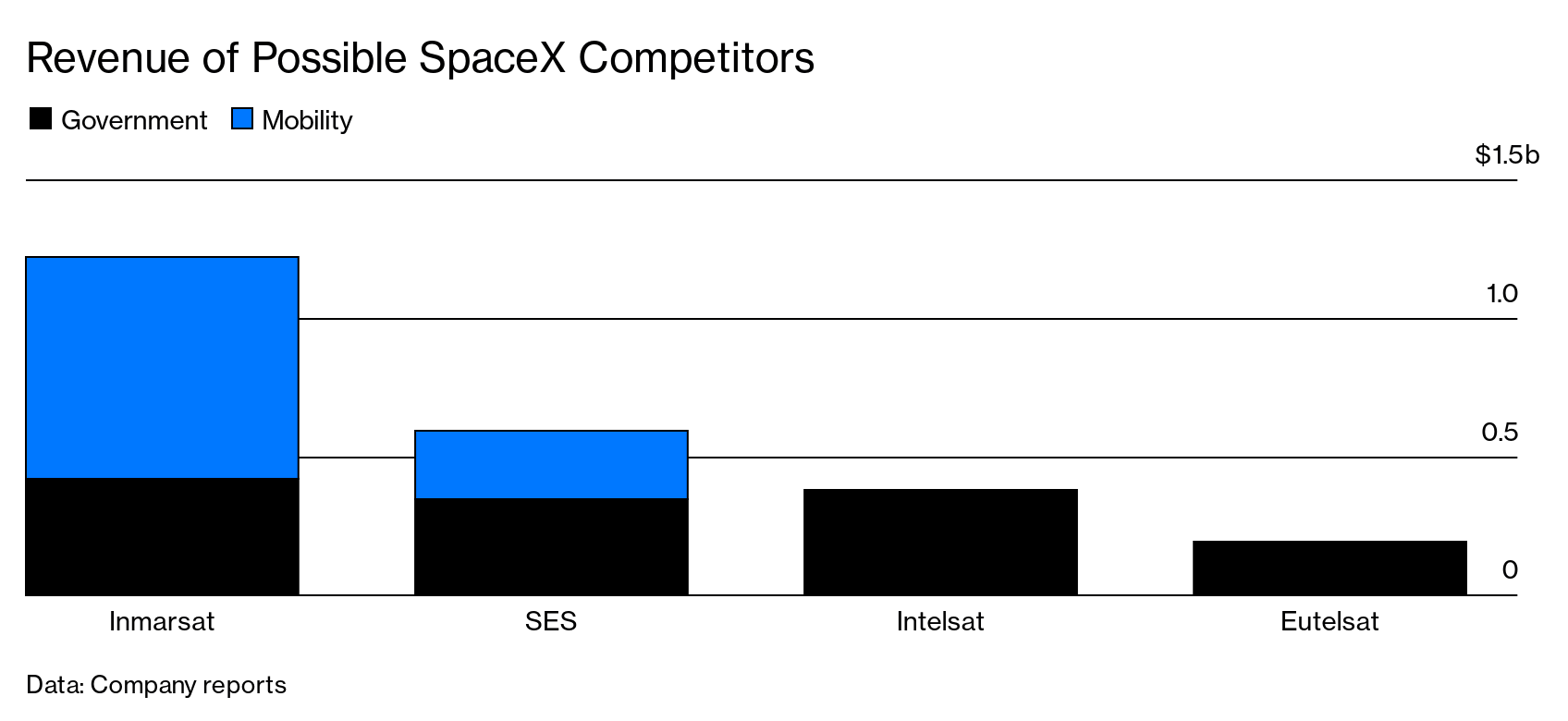

Revenue of Possible SpaceX Competitors

Data: Company reports

But a long list of past failures underscores the challenge. Low-Earth orbit, or LEO, satellites need to zip around the world at about 5 miles per second to maintain a constant altitude. To ensure a reliable internet service, a ground receiver must hop constantly from one satellite signal to another without dropping the two-way connection. It’s like playing soccer with 12 balls on the pitch. And no one has found a way to make such a sophisticated piece of new technology and turn a profit in the mass consumer market.

“There still is real uncertainty with regard to the future of these systems,” says Carissa Christensen, chief executive officer of analytics company Bryce Space & Technology. SpaceX has “an extraordinary track record of delivering technology breakthroughs,” she says, but less expertise in consumer retail markets and telecommunications. SpaceX didn’t respond to emails seeking comment.

In classic Musk style, SpaceX is drip-feeding news on the project. During the 12th Starlink launch, on Sept. 3, SpaceX engineer Kate Tice announced that the network was already achieving download speeds greater than 100 megabits per second—enough for a user to stream multiple high-definition movies simultaneously.

Musk attends an event at the SpaceX launch facility in Cameron County, Texas, on Sept. 28, 2019.

Photographer: Bronte Wittpenn/Bloomberg

Starlink threatens the entire industry because of its potential scale. SpaceX has applied to ring the planet with more than 40,000 Starlinks, about 13 times the number of active satellites in orbit. It’s targeting not only the rural broadband users of ViaSat Inc., Hughes Satellite Systems Corp., and other companies but also airline Wi-Fi providers, shipping fleets, and potential military clients—the established satellite industry’s bread and butter. Investor expectations are lofty: In July, Morgan Stanley analysts estimated that Starlink makes up $40 billion of SpaceX’s total $50 billion value.

Musk is challenging an industry that already has its back to the wall. Satellite-TV providers AT&T Inc.’s DirecTV and Luxembourg-based SES SA are under threat from terrestrial fiber-based networks powerful enough to distribute big events like soccer games reliably to millions of viewers at once. The cruise and aviation sectors are in crisis because of Covid-19, a setback for communications companies such as Inmarsat Global Ltd. and Intelsat SA that serve them.

Space communications have long been losing ground to land-based rivals. Forty years ago satellites connected long-distance voice calls. Fifteen years ago they were Africa’s main bridge to the World Wide Web. No longer. One of the industry’s most lucrative business opportunities today is selling spectrum they can no longer use to terrestrial wireless carriers. The latest casualty is OneWeb, a U.K. company that raised $3.4 billion from investors including Airbus SE and SoftBank Group Corp. on the promise of “internet access everywhere, for everyone” before filing for insolvency in March.

The project’s original champion, entrepreneur Greg Wyler, later declared the satellite industry’s role in large-scale consumer broadband “dead on arrival.” The problem, he says, is that it’s impossible for the space industry to keep pace with terrestrial network technology.

SpaceX so far has made its money by lifting others’ satellites into orbit. But Musk wants to colonize Mars, and that will cost more than he can earn in the rocket industry. He isn’t alone in believing that space broadband’s time has come. The cost of developing such projects has fallen in part because of improved computing power, smaller satellites, and more standardized parts and processes. SpaceX has an edge over rivals that rely on third parties to launch their payloads.

The world’s richest man, Jeff Bezos, is bankrolling a rival constellation project named Project Kuiper that’s yet to send up a test satellite. Telesat, a Canadian satellite company that’s been around for a half-century, is pivoting from traditional geostationary satellites into LEO to capture business with governments, airlines, and shipping companies.

Unlike SpaceX, Telesat says it will avoid the consumer market as long as there’s no low-cost, high-performance ground terminal. “We believe that in the fullness of time it will be available, but we don’t believe it’s available in the near term,” says Telesat CEO Dan Goldberg. “It’s a tough market.”

Other incumbents are steering clear of LEO entirely. The satellites offer far fewer megabits per dollar than geostationary satellites, making it harder for those systems to pay for themselves, says Inmarsat Chief Technical Officer Peter Hadinger. A geostationary satellite lasts for more than a decade, is constantly in use, and can be targeted at the busiest areas of the world. A SpaceX satellite might last only a third of that life span, Hadinger says.

Musk has promised a slender Starlink receiver that’s plugged in, breaking with the clunky dishes of the past that need a specialist to install them. Industry analyst Chris Quilty estimates the cost of the user terminal and antenna at closer to $2,000 than $1,000. “It’s really hard to compete with a bent piece of sheet metal that costs 50 bucks,” he says. “I don’t see a path for them magically breaking cost barriers that no one else has achieved.”

Quilty says he expects Musk to lobby for government work to squeeze every revenue line from Starlink. The U.S. military is one of the largest customers for satellite communications and wants to make use of the new LEO constellations. That’s partly because they offer military users a tactical advantage. Big geostationary satellites now used for battlefield communications are potential sitting ducks: A hostile actor could bring down the entire network by destroying one with a missile. Taking out several satellites in Starlink’s huge constellation, by contrast, wouldn’t compromise the system.

The plan one day is to connect the satellites directly with laser beams so data can reach across polar, oceanic, and inhospitable regions. Without this it will be hard for Starlink to serve the lucrative market for in-flight internet on long-haul planes and shipping communications. It also means SpaceX would need approval for a global array of ground stations to send data around the world. But China, Russia, and other vast territories may well freeze Musk out to antagonize the U.S. and protect their national phone companies.

Asked which competitor he would bet on if pushed, Inmarsat CEO Rupert Pearce says, “The track record would say Starlink, wouldn’t it? You’ve got the muscle of Musk, you’ve got the Silicon Valley mentality, and what they did with SpaceX is incredibly impressive.”

But if Starlink fails, it won’t just burn SpaceX’s own investors. “If Starlink is a deep disappointment,” says industry consultant Tim Farrar, who’s advised investors on other satellite projects, “you could see another downturn in the space investment cycle.”

BOTTOM LINE – It’s hard to bet against the billionaire founder of Tesla, but space is a perilous battlefield, and the history of the satellite business is full of failures.